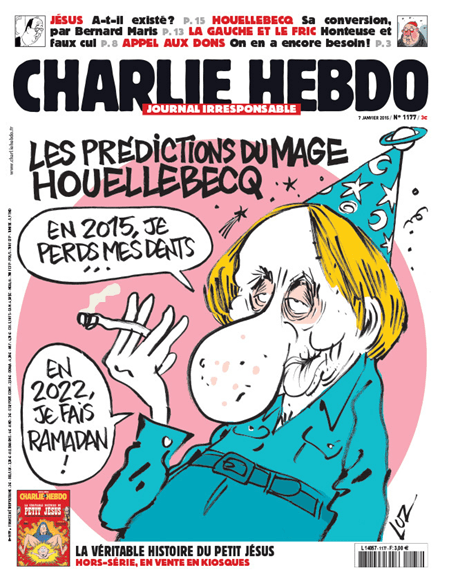

That morning, the bold French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo hit the newsstands

with a new cover featuring controversial, contemporary author Michel Houellebecq

as the “Mage Houellebecq”.

That same day, Houellebecq’s “political fiction” [i] novel, Soumission, was released in bookstores.

And at 11.30am, two Islamist gunmen stormed the Paris office of Charlie Hebdo, murdering twelve people – including publishing director Charb and many of France’s most famous cartoonists – in retaliation for the magazine’s mocking depictions of the Prophet Muhammad.

In an instant, the magazine cover was transformed from a satirical depiction of a controversial author’s recent work, into an uncanny, prophetic artefact. The mirroring of a novel, onto mass media, coinciding with real-time tragedy, emphasised the intertwined relationship between the intellectual and the mass media, presenting the question: can satire and provocation stand in as intellectual engagement?

Charlie Hebdo

7 January, 2015

TRANSLATING SOUMISSION: LITERALLY AND VISUALLY

With a wrinkled face, sunken eyes, and a cigarette between his fingers, this is a distinctive, Charlie Hebdo caricature of Michel Houellebecq. The image works as meta-commentary, where “en 2015, je perds mes dents… en 2022, je fais Ramadan” acts as a direct commentary on the narrative of Michel Houellebecq’s 2015 novel, Soumission.

Set in the future 2022, Soumission –which, translated into English is Submission, and, notably, is “just the literal translation of the Arabic word Islam” [ii] -sees Marine Le Pen lose the presidential election to the fictional leader of the new Muslim party in France, ‘Mohammed Ben Abbes’. With this new leader, France becomes an Islamic society, and thus Houellebecq depicts a nation without liberty, freedom of speech, and where women must leave the work force and wear a veil [iii].

In this novel, for better or for worse, Houellebecq certainly takes advantage of the intellectual’s duty to defend freedom of expression and the “right to offend” [iv]. Alongside an emphasis on upholding laïcité, Houellebecq’s novel directly echoes Charlie Hebdo‘s notorious satirical rhetoric, which “soulève régulièrement la polémique” [v], as they share a commitment to provocation as a form of critique

PARRHESIA

On the cover of the magazine, Charlie Hebdo presents Houellebecq as not just a novelist or an intellectual, but also as a humorous media figure, or even a ‘magician’. Wearing a wizard’s hat on his starry head, under the headline “LES PRÉDICTIONS DU MAGE HOUELLEBECQ”, the correlation between Houellebecq and Nostradamus, the sixteenth century French astrologer and ‘seer’ of future events, is unmistakeable.

Like Nostradamus, Houellebecq predicts the future of France, and uses his novel as a vessel for social critique, against Islamic influence threatening to destroy freedom of speech. In this sense, Charlie Hebdo and Houellebecq embrace “Parrhesia”. French philosopher and intellectual Michel Foucault describes Parrhesia as “le courage de la vérité chez celui qui parle et prend le risque de dire, en dépit de tout, toute la vérité qu’il pense, mais c’est aussi le courage de l’interlocuteur qui accepte de recevoir comme vraie la vérité blessante qu’il entend ” [vi]. Charlie Hebdo and Houellebecq demonstrate this speaker’s courage by articulating their provocative ‘truths’, through the mediums of dystopian fiction and satirical press. As a result, their work receives media coverage, forcing French society to listen, and fulfilling Parrhesia.

DÉTOURNEMENT

Charlie Hebdo‘s journalistic approach, though controversial, operates differently from Houellebecq’s literary provocations. The magazine filters, and arguably softens Houellebecq’s ‘real’ critiques of religious society through its rhetorical discourse of humour and satire. The unflattering, yet distinctive cartoon of Houellebecq himself mocking the idea of “Je fais Ramadan!” demonstrates a modern form of intellectual engagement – satire. Using satire to engage with Houellebecq’s ideasallows Charlie Hebdo to perform a critical intervention, speaking truth to power in a way that, as The Guardian‘s cartoonist Steve Bell notes, is “less easy to say in a more straightforward journalistic context” [vii]. It is easier to make social commentary, particularly social criticism, behind the lens of satire.

Thus, while Houellebecq and Charlie Hebdo have often been accused of similar transgressions, such as Islamophobia and racism, the magazine’s mockery of the author sets them apart, and demonstrates a form of satirical détournement. In his book La Société du Spectacle, French Marxist theorist Guy Debord presents this idea of détournement, as “the flexible language of anti-ideology” [viii]. In this sense, Charlie Hebdo does not simply broadcast Houellebecq’s provocation, but satirically ‘reimagines’ or ‘reroutes’ it. The magazine reframes his message, potentially mocking Houellebecq and his ‘visions’, and thus asserting the media’s power to question not just the intellectual’s ideas, but his very credibility.

PUBLIC FIGURE ☑ THINKER ☑ AUTHOR ☑ INTELLECTUAL □…?

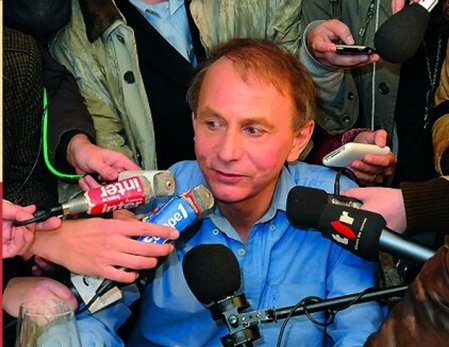

A satirical, controversial, public figure, thinker, and author – but a stark contrast from a traditional intellectuel engagé. This prompts the question: by what criteria does Michel Houellebecq qualify as an intellectual?

Michel Houellebecq, 2015, Andreu Dalmau

Neither Charlie Hebdo nor Michel Houellebecq embody the traditional voice of the intellectual – one who would offer solutions and expertise to political problems. Instead, their work presents itself more as social commentary than solution. However, this very commentary often defends laïcité, appeals for justice and acts as a Sartrean voice of emancipation and enlightenment [ix]. After the 2015 shootings, the lives of Michel Houellebecq and employees at Charlie Hebdo were threatened,yet the magazine and Soumission continued to be published, demonstrating their Parrhesia, and refusal to be silenced.

As its cartoons suggest, Charlie Hebdo does not strive to be a formal newspaper, but instead an outlet for fresh and satirical depictions of heavy topics. Similarly, despite calling for social justice, Houellebecq doesn’t present himself as the traditional intellectuel engagé, who directly intervenes in political causes and speaks truth to power. In fact, despite his work being described by Radio Canada as “satire politique efficace et hautement dérangeante” [x], Houellebecq has made his scorn for the politically committed intellectual clear. He does not want to be a traditional Sartrean intellectual – he has “toujours détesté l’idée que les écrivains prennent des positions politiques” [xi]. Thus, the affinity between the untraditional Houellebecq and boundary-pushing Charlie Hebdo is a logical pairing.

SOCIAL CHANGE

So, whilst Houellebecq is not the typical intellectuel engagé, both Houellebecq and Charlie Hebdo are absolutely actively involved in political and social causes, using their platforms for social analysis, commentary and controversy. In explaining the necessity for the intellectuel spécifique, one who uses their expert knowledge within a specific field, rather than speaking as a universal moral conscience, Foucault decides, “universal systems of morality no longer provide effective responses to social and political problems” [xii]. Although Houellebecq does not have the academic background to be considered an intellectuel spécifique, it could be said that his version of the satirical and provoking intellectual speaks to a more proactive, and effective, coming of social justice. For example, Houellebecq’s method is provocation; he offers few solutions but amplifies societal anxieties. The content of Charlie Hebdo has similar effects, it sparks controversy, but it also translates into direct action. Its satirism mobilises public debate, shapes political discourse, and forces confrontation, like a traditional intellectual, as seen in the political movement following the 2015 shootings.

Gravity Media, 2015

The ‘Je Suis Charlie’ movement became a global phenomenon, emerging just hours after the attack. The slogan, meaning “I am Charlie”, was first used on social media by journalist Joachim Roncin and swiftly went viral, transforming from an expression of grief and solidarity into a powerful, collective defence of freedom of speech and the right to satirize. Millions adopted it in online posts, in marches across France, and was then featured on the next cover of Charlie Hebdo, establishing the phrase as a defining statement against religious intimidation.

Charlie Hebdo, 14 January 2015

Foucault would see this global movement as an ‘effective response’, directly affecting the public’s perception of social movements. Thus, despite straying from the classic role of the intellectuel engagé or intellectuel spécifique, the role of the modern intellectual is embodied by provocateurs like Houellebecq and Hebdo, who take action, covering both media and literature.

THE SYMBIOSIS OF PROVOCATION

The intermediality between Houellebecq’s novel and Charlie Hebdo’s magazine cover demonstrates the symbiotic relationship, and the constant mirroring, between the intellectual and the mass media.

The cover itself acts as a site of intermediality by combining the medium of satirical cartoon with the medium of the literary intellectual – two “separate material vehicles of representation” [xiii]. Houellebecq and his ‘prédictions du mage’ of Soumission provide the literary framework, while Charlie Hebdo delivers the visceral, populist punch. This fusion creates a symbiosis of provocation, since both Houellebecq and Charlie Hebdo are professional provocateurs, who challenge French secular society to uphold laïcité. The magazine cover acts as a point of convergence, where the ‘vehicle’ of satirical art meets the ‘vehicle’ of literary and philosophical thought.

Michel Houellebecq on 8 November, 2010.

REUTERS via Benoît Tessier.

In this sense, Houellebecq and Hebdo rely on each other.

Without his caricature, speech bubbles, and magic hat, Michel Houellebecq would not have his full public voice, or persona. As an intellectual, his reputation and celebrity aspect are directly correlated to the way in which the media, such as Charlie Hebdo, frames and entertains his ideas. His work gains more cultural traction with personality attached to it, and thus the mass media fulfils the intellectual’s need for public legitimacy. Conversely, Charlie Hebdo requires the flame to feed the fire. The media relies on conversation starters such as Michel Houellebecq, whose provocative ideas provide the fuel for its satirical social commentary.

This co-dependent, symbiotic relationship between the media and the intellectual directly responds to Jean-Paul Sartre’s command to each intellectualto embrace the mass media. In his book Qu’est-ce que la littérature, Sartre insists that “Il faut apprendre à parler en images, à transposer les idées de nos livres” [xiv]. To maximise the audience is to maximise the influence. The commercial success of Soumission, which sold a total of 120,000 copies in its first five days in France, stands as a testament to this logic. This statistic demonstrates how the triangulation of the novel, its satirical mediation on Charlie Hebdo’s cover, and the media coverage of the shooting propelled Houellebecq’s ideas into the public sphere, with unprecedented, and arguably undeserved force.

THE INEXTRICABLE LINK

In this intermedial circuit, Houellebecq’s initial literary provocation was magnified by Charlie Hebdo’s visual satire, which in turn was violently answered by an event that mirrored the novel’s own themes. Demonstrating satire as a strong form of intellectual engagement, the Charlie Hebdo magazine offers a critical lens, which, “is of the essence of cartoons, and of comedy, generally, that they will offend someone” [xv]. This offensive, boundary-pushing quality is not a failure but its function—suggesting that a modern intellectual can be “someone who meddles in what is not his business” [xvi], and sheds light on critiques, opinions and injustices.

The Charlie Hebdo cover, and the events that followed, highlight a new intellectual model; one that embraces provocation, and utilises the mass media as its enabler. Michel Houellebecq, the ‘mage’, predicted a France transformed by ideological conflict; Charlie Hebdo illustrated it; and the terrorist attack confirmed its urgent relevance.

On Wednesday 7 January 2015, the relationship between the intellectual, their message, and various mediums of novel, magazine and illustration proved to be inextricably linked, speaking truth to power in a world of blurred lines between fiction, satire and reality.

ENDNOTES

[i] Bourmeau, 2015

[ii] Rosenthal, 2015, p.76

[iii] Armus, 2017, p.128

[iv] Larkin, 2016, p.193

[v] Radio Canada, 2015

[vi] Foucault, 2009, p.14

[vii] Byrne, 2010.

[viii] Debord, 1967, p.110

[ix] Sartre, 1948

[x] Radio Canada, 2015

[xi] Bowd, 2019 p.40

[xii] Gutting, 2005, p.23

[xiii] Jensen, 2016, p.972

[xiv] Sartre, 1948, p.266

[xv] Larkin, 2016, p.196

[xvi] Sartre, 1976, p.230

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND FURTHER READING

ÅGERUP, K. (2020). Submission beyond Islam: Yielding as Organizing Principle in Michel Houellebecq’s novels. The Comparatist, [online] 44, pp.196–214. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26975031 [Accessed 2 Nov. 2025].

Armus, S. (2017). Trying on the Veil: Sexual Autonomy and the End of the French Republic in Michel Houellebecq’s ‘Submission’. French Politics, Culture & Society, [online] 35(1), pp.126–145. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44504256 [Accessed 23 Oct. 2025].

Bourmeau, S. (2015). Scare Tactics: Michel Houellebecq Defends His Controversial New Book. [online] The Paris Review. Available at: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/01/02/scare-tactics-michel-houellebecq-on-his-new-book/.

Bowd, G. (2019). The Anti-Sartre? Michel Houellebecq and Politics. Australian Journal of French Studies, 56(1), p.40. doi:https://doi.org/10.3828/AJFS.2019.2.

Byrne, J. (2010). ‘Bringing the satirical napalm to the party’. The Irish Times. [online] 21 Aug. Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/art-and-design/bringing-the-satirical-napalm-to-the-party-1.640988 [Accessed 19 Oct. 2025].

Debord, G. (1967). The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by K. Knabb. [online] Canada: Bureau of Public Secrets. Available at: https://files.libcom.org/files/The%20Society%20of%20the%20Spectacle%20Annotated%20Edition.pdf.

Foucault, M. (2009) Le Courage de la vérité. Paris: Gallimard/Le Seuil.

Gutting, G. (2005). Foucault – A Very Short Introduction. [online] Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://ia902905.us.archive.org/27/items/gary-gutting-foucault-a-very-short-introduction/Gary%20Gutting%2C%20Foucault%20A%20Very%20Short%20Introduction.pdf [Accessed 16 Oct. 2025].

Jensen, K.B. (2016). Intermediality. In: The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy, p.972.

Larkin, F. (2016). Free Speech and ‘Charlie Hebdo’. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, [online] 105(418), pp.192–198. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24871663 [Accessed 23 Oct. 2025].

Radio Canada (2015). Nouveau Houellebecq : parution sous haute surveillance. [online] Radio-Canada. Available at: https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/700994/nouveau-roman-houellebecq-parution-sous-tension [Accessed 2 Nov. 2025].

Rosenthal, J. (2015). Houellebecq’s ‘Submission’: Islam and France’s Malaise. World Affairs, [online] 178(1), pp.76–84. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43555285 [Accessed 23 Oct. 2025].

Sand, S. (2020). La fin de l’intellectuel français ? – De Zola à Houellebecq. La Découverte.

Sartre, J.-P. (1948). Qu’est-ce que la littérature? [online] Paris: Gallimard. Available at: https://archive.org/details/questcequelalitt0000jean/mode/2up [Accessed 30 Sep. 2025].

Sartre, J.-P. (1976). ‘A Plea for Intellectuals’, in Between Existentialism and Marxism. New York: William Morrow, pp.228–285.