Les Nouveaux Philosophes were a group of intellectuals who came to prominence in the late 1970s, headed by the iconic figure of Bernard-Henri Lévy. Despite extensive criticism of their philosophy, the Nouveaux Philosophes were successful in building notoriety in the media. Notably, their television presence proved crucial in building their image and spreading their ideas (Chaplin, 2007).

There were several points of convergence amongst the Nouveaux Philosophes. They rejected Marxism, the dominant ideology, as totalitarian, seeking to break away from the oppression of ideological schemes and their ineffective theoretical justifications for suffering (Dews, 1980). Their pessimistic philosophy created a more pragmatic conception of politics, moving away from these complex frameworks, towards an ethical basis intended for taking action (Hazareesingh, 1991).

This ostensibly worthy cause was met with severe backlash by many intellectuals. Their philosophy was criticised for relying on abstract concepts filled with oversimplifications of complex issues (Deleuze, 1977), and for being a symptom of societal disillusionment, not a real political movement (Negt & Daniel, 1983).

Consequently, their rise to prominence generated concern amongst intellectuals about the impact that the media was having on thought, and the narrowing of the intellectual arena. For some, this mediatised personality was a point of no return in the denaturing of the intellectual (Chaplin, 2007).

Many of these issues were addressed directly in an engaging episode of the live television debate show Apostrophes (Apostrophes, 1977), which pitted Lévy and André Glucksmann of the Nouveaux Philosophes against two of their critics, François Aubral and Xavier Delcourt.

Images Speak Louder Than Words

What then, did this problematic philosophy do to warrant so much media attention? It can be attributed partly to the fact that their style of thought aligned with the affordances of the audio-visual medium.

Cultivating an image became an increasingly important aspect of visual media. Within Apostrophes the idea of appearance is inescapable due to the prolonged up-close shots analysing the speaker’s demeanour. Lévy arguably navigated this better than anybody else. He cultivated an iconic image which captivated the press through his characteristic look of cigarette in hand, tousled hair and dramatically open shirt. Whilst this consolidated him as a favourite on the small screen, it was also seen as the most intellectually damming aspect of the medium (Chaplin, 2007). The focus on appearance over substance created a demand for philosophy which was completely extrinsic to the work. The media wanted the man, not the mind.

The desire for the intellectual’s image is evident as it is made synonymous with the work by replacing the cover art with the live feed of the authors.

The title of the work is equated to their image as the visual aspect is inseparable from the print. The visual distractions become the embodiment of the authorship and therefore also infringe on the work itself as autonomous art, since the focus goes beyond the merits of the text (Grishakova, 2024)

. Combining several ‘material vehicles of representation’ shows the mounting inescapability of Intermediality for the intellectual (Jensen, 2016), no longer able to hide behind their work, amidst increasingly complex communicative relationships.

Pay to Play

Marketing, therefore, was an essential aspect to mastering television as image was inescapable. Although, this characteristic extends beyond just image, as the marketability of ideas was also central for achieving publicity and success. The rise of mass media had shifted the power dynamics such that the intellectual work was now less valuable than the media. This relationship created the style of ‘interview-thought’ (Deleuze, 1977) which required intellectuals to forego their autonomy since they, as subjects, would be under the panoptic constraints of the media (Bourdieu, 1996).

The Nouveaux Philosophes have been criticised of submitting to this by embracing the ideologies of the media, and adopting ideas in the intent of crafting a self-serving narrative (Ross, 2022). Concerningly, it is reminiscent of the criticism made by Julien Benda in ‘La Trahison des Clercs’ which focused on intellectuals conforming to the influence of the bourgeois class in order to foster their personal interests (Halimi, 1997), rather than upholding their integrity as intellectuals.

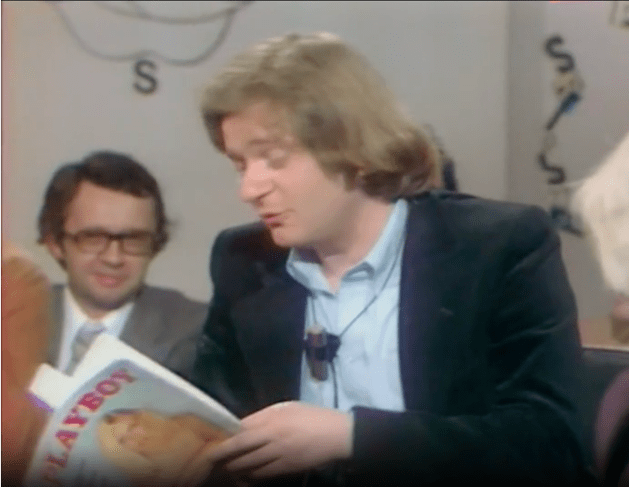

Giles Deleuze is scathing in his contempt for this lack of authenticity, as he believes that the Nouveaux Philosophes constitute something completely separate to what can be called philosophy. He sees them no longer as creators, but servants to the media (Deleuze, 1977). To demonstrate this, François Aubral this by produces a copy of the magazine ‘Playboy’, to which Lévy has contributed, as an example of chasing media attention and trends.

There is a conflict of material raised here, between the captivating image that Lévy presents, and his textual persona, implicated in a magazine prioritizing it’s accessibility and entertainment. Whilst his printed material is infringing upon the respectability of his visual image, the magazine contribution also shows that Lévy recognises pride is not a trait intellectuals can afford to cling to anymore. Ultimately they need the media more than it needs them.

This polarising approach to producing philosophy in the public sphere meant that inevitably the more marketable and public minded intellectuals, such as Lévy, would benefit from the spotlight, whereas others would end up being passed over. In this sense, it created a somewhat closed arena built around the politics of mediatisation (Rieffel, 1993).

A consequence of this was the distortion of authority within the intellectual field, biasing those with more visibility and reinforcing their dominance (Bourdieu, 1984)

. Xavier Delcourt addresses this directly. He believes it threatening for intellectuals that such an empty philosophy has received so much attention, at the cost of others, excluding them from the public discourse [00:35:45]. The frustration at this is palpable from François Aubral, who repeatedly shouts at Lévy “Vous êtes un genie de publicité” [01:00:03], in an effort to reprimand him for an undeserved and strategic position in the spotlight.

Is it Hot in Here?

The aggression that was conveyed through this discourse was a trait of the Apostrophes episode as a whole. The debate in Apostrophes was structured as an end in itself, rather than as a part of wider dialogue, as the entertainment from this genre of television debate came from the conflict (Chaplin, 2007). The dramatic mise-en-scène of the show helped this by cultivating a tense atmosphere amongst the guests as they faced off against each other in an adversarial formation.

Structurally, the show was also designed to build tension. Guests would present their ideas and criticisms in an interview format, one-by-one, before the debate ensued. This allowed early blows to be landed and the fire to be stoked in the build-up to the climax of the show. It succeeded in its aim as André Glucksmann could not resist trying to interject and voice his frustration before the debate had even started [00:32:40].

The entertainment driven format sacrificed the rigour of the intellectual discussion and it led to an oversimplification of complex issues. The medium of television therefore relied on a ‘fast thinking’ which focused on easily digestible opinions, sensationalist discussion and the distortion of ideas into a ‘fast-food culturel’ (Bourdieu, 1996). Whilst, therefore, shows such as Apostrophe tried to make the idea of the literary salon open to the public, they had merely succeeded in turning it into a boxing ring (Chaplin, 2007).

There was no shortage of cutting blows in this particular episode of Apostrophes. The tensions spilled over on multiple occasions, with the presenter, Bernard Pivot, trying to raise his voice and regain control amidst the disorder. Apart from in Fig.7, where he in fact looks off-set and repeatedly puffs his cheeks out, exhausted by the relentless conflict, deciding to let it run. The camera switches to a voyeuristic angle behind the audience to capture this, as if hidden. The retreat to this more secretive position not only captures the disorder in its entirety, but the obscured view also makes the viewers feel as though they are getting an exclusive look behind the curtain, typically reserved for the in-person audience. Happening live, this raw and unalterable conflict can be exploited as a rich source of entertainment to draw in the viewers.

At What Cost?

Television shows such as Apostrophes opened a whole new sphere for intellectuals to operate in. It expanded their reach to a much larger audience, generated greater interest in philosophy and helped to influence ethical change in society.

However, there was undoubtedly a price to making culture more entertaining. Lévy recognised that the control of the intellectual’s ideas now belonged to the media, which meant conforming to their sound-bite style in order to achieve publicity and success. This transformation of philosophers into media figures depended more on their image and marketability than the intellectualism, and marked a potentially irreversible departure from their traditional status. In a sink or swim environment, the intellectual had to embrace change, or risk being left out in the cold.

Television shows such as Apostrophes opened a whole new sphere for intellectuals to operate in. It expanded their reach to a much larger audience, generated greater interest in philosophy and helped to influence ethical change in society.

However, there was undoubtedly a price to making culture more entertaining. Lévy recognised that the control of the intellectual’s ideas now belonged to the media, which meant conforming to their sound-bite style in order to achieve publicity and success. This transformation of philosophers into media figures depended more on their image and marketability than the intellectualism, and marked a potentially irreversible departure from their traditional status. In a sink or swim environment, the intellectual had to embrace change, or risk being left out in the cold.

Further Reading

Apostrophes, 1977. Les Nouveaux Philosophes, sont-ils de droite ou de gauche? [Interview] (27 May 1977).

Bourdieu, P., 1984. ‘ Le hit-parade Le hit-parade – Alternative Formats des intellectuels français, ou Qui sera juge de la légitimité des juges?. In: Homo Academicus. Paris: Minuit.

Bourdieu, P., 1996. Sur la Télévision. Paris: Raisons d’Agir.

Chaplin, T., 2007. Turning on the Mind: French Philosophers on Television. 1st ed. s.l.:The University of Chicago Press.

Deleuze, G., 1977. A Propos des Nouveaux Philosophes. Minuit, May.

Dews, P., 1980. The New Philosophers and the End of Leftism. Radical Philosophy, Volume 24.

Grishakova, M., 2024. Intermediality: Introducing Terminology and Approaches in the Field. In: The Palgrave Handbook of Intermediality. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 13-29.

Halimi, S., 1997. Les Nouveaux Chiens de Garde. 1st ed. Paris: Liber-Raisons d’Agir.

Hazareesingh, S., 1991. Intellectuals and the French communist party : disillusion and decline. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Jensen, K. B., 2016. Intermediality. In: The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy. s.l.:Wiley-Blackwell.

Johnson, C., 2003. The genre of the Interview. Nottingham French Studies, 42(1), pp. 1-4.

Negt, O. & Daniel, J., 1983. Reflections on France’s Reflections on France’s – Alternative Formats ‘Nouveaux Philosophes’ and the Crisis of Marxism. SubStance, 11(4), pp. 56-67.

Rieffel, R., 1993. La Tribu des Clercs. s.l.:Calmann-Lévy CNRS Editions.

Ross, K., 2022. Philosophers on Television. In: May 1968 and Its Afterlives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.