In a theatrical altercation that unfolded between the pages of a literary magazine, the friendship between Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus came to a sudden end. Sartre’s vitriolic letter to Camus that notoriously extinguished their friendship is here re-examined in light of its significance as an open letter in Les Temps Modernes. This journal, the leading intellectual ‘revue’ of the time, put their private dispute onto public turf, and the extension to wider audiences is not accidental: Sartre’s choice to put their quarrel in print reinforced their polarised standpoints and their celebrity status in the public imagination. How Sartre presents their insurmountable divide and dismantles Camus’s credibility as an ‘intellectuel engagé’ in his letter merits a closer look.

A Friendship on the Rocks

Sartre and Camus became friends in 1943 and it was only several years later that cracks began to show and their philosophies diverged. Their disagreement centred around the ethics of violence, a debate which was illuminated during the rise of communism and the subsequent release of information on Soviet terror in the early 1950s.

Camus’s L’Homme Révolté (1951)[i] condemned any act of violence or murder and denounced anyone who exonerated communist violence as a means to an end. Camus’s doctrine of non-violence cemented Sartre’s opposing stance on revolutionary realism, with him condoning the use of violence as a legitimate response to oppressive forces and justifying communism as a necessary step to defeating capitalism.

Sartre, editor-in-chief of Les Temps Modernes, decided that one of his junior editors, Francis Jeanson, should review Camus’s novel. Camus was outraged by the review’s brutal assault on his philosophy, and by what he saw as a slight from Sartre who had delegated the review to Jeanson. Camus’s response was addressed to Sartre, (entitled ‘Lettre au Directeur au Temps Modernes’[ii]) who he deemed was the true culprit behind the review, and was printed in the August edition of Les Temps Modernes.

The Battleground of Correspondence

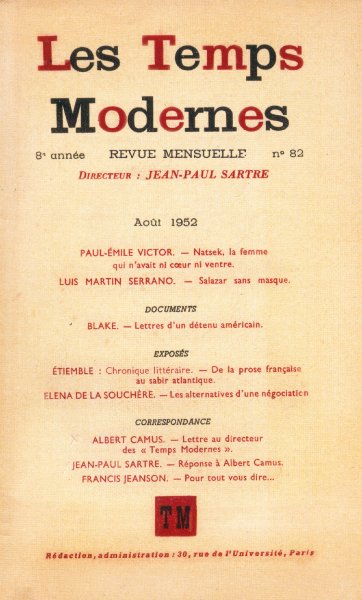

Sartre responded in the same edition. It might be surprising to look at the front matter (Fig. 2) and see that what became an infamous intellectual quarrel first appeared very innocuously as ‘correspondance’ at the end of the journal.

Ronald Aronson calls Les Temps Modernes ‘unlikely terrain’[iii] for this argument to play out, but is it really? The journal was under Sartre’s direction (as emphasised in capital letters at the top of the page) which gave him ultimate agency over the debate. It was his choice to employ Jeanson to write the incendiary review, which could have been a manoeuvre to retain respectful distance from the diatribe, or alternatively was an act of petty provocation. For Camus, how better to admonish his opponent than to criticise him in the very journal that he runs?

Fig. 2 : Les Temps Modernes, 82, August 1952

The Gloves Come Off[iv]

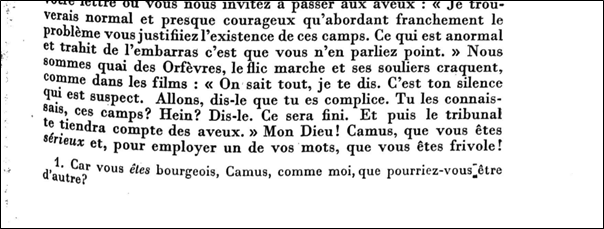

Sartre’s ‘Réponse à Albert Camus’[v] (Fig. 3) opens with an amiable tone: ‘mon cher Camus.’ In antithesis to Camus’s detached address, ‘Monsieur le Directeur’, Sartre’s salutation does not hide behind formalities and addresses Camus by name, his endearment highlighting their close relationship. However, the suggestion that this is a compassionate letter is deceptive. In fact, it is the most scathing correspondence yet.

The use of the epistolary form, due to its conventions like direct address, rhetorical questions, salutation and valediction, carries an intimate and personal aspect which is lost in other media. The blurred boundary between letter and article produces an intermedial quality that facilitates the projection of their personal dispute onto a public stage.

‘Notre amitié n’était pas facile mais je la regretterai. Si vous la rompez aujourd’hui, c’est sans doute qu’elle devait se rompre.’ Immediately, Sartre places the responsibility for their estrangement on Camus, ironic given the onslaught of criticism that he later unleashes. Sartre, at first, writes nostalgically about their relationship in which ‘beaucoup de choses nous rapprochaient, peu nous séparaient.’ He quickly reverses this tone by describing how friendship often succumbs to a totalitarian framework in the way that quarrels arise in the absence of agreement. Sartre alludes to the root of their conflict: their diverging views on violence.

Sartre references Camus’s preceding letter multiple times throughout his twenty-page response and justifies his reaction as a consequence of Camus’s ‘ton si déplaisant’, necessitating his reply. The intertextuality is particularly effective since the letters are placed consecutively in the same volume, making it even more engaging for the contemporary reader who could flick back and forth to find the quotations that Sartre manipulates and uses against Camus.

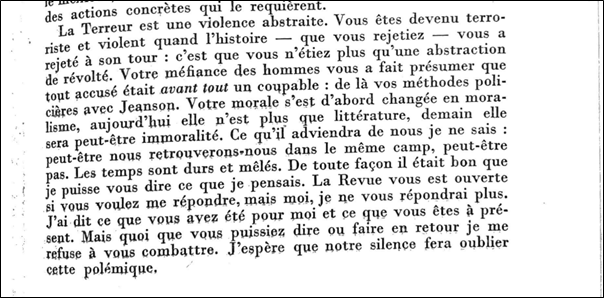

Sartre uses footnotes to reiterate his ideas (Fig. 4), belligerently reminding Camus that he can no longer rely on his Algerian origins to legitimise his role as a spokesperson for the oppressed. The separation of footnote from text creates another focal point, drawing the gaze down the page. This journalistic affordance, transgressing the border between letter and article, allows Sartre to taunt Camus on all parts of the page and corners Camus: he cannot escape Sartre’s attempts to discredit him as an ‘intellectuel engagé’.

The term ‘intellectuel engagé’ emerged in Sartre and De Beauvoir’s essay, ‘Qu’est-ce que la littérature’[vi] which stressed the role of the writer as witness of their times whose responsibility was to speak truth to their audience. Sartre sees Camus’s incapacity to support or identify with any current revolutionary struggle as a shirking of this responsibility and a failure of the ‘intellectuel engagé’. Worse, he accuses Camus of being part of the oppressive class he has historically opposed. The interrogative at the end ‘que pourriez-vous être d’autre?’ fixes his identity to the bourgeois, denying Camus the separation between him and them, a sly jibe from Sartre.

The final blow arrives at the end when Sartre declares Camus has become a ‘terrorist’ for his rejection of history and inaction in the face of current conflict. Reading this emotionally charged rhetoric, it is not surprising that some critics, like Daniel Berthold, have described this twenty-page tirade as a ‘character assassination’[vii] of Camus. Sartre goes beyond politics and philosophy, and completely discredits Camus’s morality. He disputes Camus’s right to be deemed an ‘intellectuel engagé’, seeing his rejection of violence as a bypassing of responsibility allowing him to recline on a moralistic high horse. Sartre, who advocates parrhesia – speaking truth to power – condemns Camus’s passivity as an act of ‘terrorism’. To sever any hope of reconciliation, Sartre states that even should Camus reply, he will no longer continue their correspondence. This establishes Sartre’s authority over the conversation: he has demonstrated not just to Camus, but to the thousands of readers, that he has the last word.

The Open Letter: a Weapon of Words

So why choose a journal over another medium? Radio had emerged onto the scene and was being used by Les Temps Modernes as early as 1947 to appeal to mass audiences. Therefore, there was a deliberate choice to keep this altercation confined to the smaller audiences – the ‘revue’ only had a circulation of approximately 10,000 – and contain the quarrel within the parameters of paper. Perhaps this is a last signal of respect from the opponents, for whom criticising each other on more popular platforms might have been stooping too low. Alternatively, it is easier to hide behind acerbic words in printed press than it is to vocalise them live to audiences. The radio may threaten the theatrical illusion of the feud, whereas the printed word creates a permanence, a story to be read and retold. These celebrity characters hold more power behind this shroud, allowing them to deepen their hold in the public imagination.

Sartre’s open letter was a remarkable weapon: page by page he shattered Camus’s integrity as an ‘intellectuel engagé’, rendering what could have been a stern argument between friends a public humiliation in the French press. By airing their grievances in an intellectual journal, their struggle went beyond their diverging philosophies on violence, becoming a battle of control over the intellectual terrain. Had their disagreement not been so public and not polarised them into intellectual antagonists, perhaps their split would not have been so definitive.

Appendix

Fig. 1 : Cover image from: Joël Calmettes, dir., Sartre Camus: a Fractured Friendship (Arte, 2014)

Fig. 2 : Les Temps Modernes, 82, August 1952

Fig. 3,4,5: Jean-Paul Sartre, ‘Réponse à Albert Camus’, Les Temps Modernes, 82, August 1952

Further Reading

Aronson, Ronald, Camus & Sartre : the story of a friendship and the quarrel that ended it (University of Chicago Press, 2004)

———————, ‘Camus versus Sartre: The Unresolved Conflict’, Sartre Studies International, 11.1/2 (2005), pp. 302–10

Berthold, Daniel, ‘Violence in Camus and Sartre: Ambiguities’, The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 59.1 (2021), pp. 47–65

Birchall, Ian H., Sartre against Stalinism (Berghahn Books, 2004)

Camus, Albert, L’Homme Révolté (Gallimard, 1951)

——————-, ‘Lettre au directeur des Temps Modernes’, Les Temps Modernes, 82, August 1952

Duvall, William E., ‘The Sartre–Camus Quarrel and the Fall of the French Intellectual’, The European Legacy, 16.5 (2011), pp. 579–585

Fleming, Michael, ‘Sartre on Violence: Not So Ambivalent?’, Sartre Studies International, 17.1 (2011), pp. 20-40

Forsdick, Charles, ‘Camus and Sartre: The Great Quarrel’, in The Cambridge Companion to Camus, ed. by Edward J. Hughes (Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 118–30

Martin, Andrew, ‘Gloves off’, in The Boxer and The Goal Keeper: Sartre Versus Camus (Simon and Schuster, 2012)

Mattéi, Jean-François, ‘Camus et Sartre : De l’assentiment Au Ressentiment’, Cités, 22 (2005), pp. 67-71

Moody, Alys, ‘“Conquering the Virtual Public”: Jean-Paul Sartre’s La tribune des temps modernes and the Radio in France’, in Broadcasting in the modernist era, ed. by Matthew Feldman et al. (Bloomsbury, 2014), pp. 245-265.

Sartre, Jean-Paul, ‘Qu’est-ce que la littérature’ (Éditions Gallimard, 1948)

———————-, ‘Réponse à Albert Camus’, Les Temps Modernes, 82, August 1952.

Zaretsky, Robert D., ‘Chapter Three: 1952, French Tragedies’, in Albert Camus : Elements of a Life (Cornell University Press, 2010), pp. 79-119

Endnotes

[i] Albert Camus, L’Homme Révolté (Gallimard, 1951).

[ii] Albert Camus, ‘Lettre au directeur des Temps Modernes’, Les Temps Modernes, 82, August 1952.

[iii] Ronald Aronson, Camus & Sartre : the story of a friendship and the quarrel that ended it (University of Chicago Press, 2004), p. 2.

[iv] Adapted from Andrew Martin, ‘Gloves off’, in The Boxer and The Goal Keeper: Sartre Versus Camus (Simon and Schuster, 2012).

[v] Jean-Paul Sartre, ‘Réponse à Albert Camus’, Les Temps Modernes, 82, August 1952.

[vi] Jean-Paul Sartre, ‘Qu’est-ce que la littérature’ (Gallimard, 1948).

[vii] Daniel Berthold, ‘Violence in Camus and Sartre: Ambiguities’, The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 59.1 (2021), pp. 47–65, (p. 49).