Over the last century, the French intellectuel has been defined and redefined by many different thinkers across many, often contrasting, categories. I believe that French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson is firmly an intellectuel, and while his work may lack in words, it is anything but silent. Jean-Pierre Montier has written extensively on Cartier-Bresson’s intellectuel status, and I would like to extract and contextualise some of his arguments. He defines the intellectuel as an outsider, neither expert nor profit, but an “empirical” visionary that provides us with perspective[i].

For Montier, Cartier-Bresson’s work lies of outside politics and shows us simply “men and women”[ii]. Cartier-Bresson calls himself an “eye”, and in his work Apropos USSR (1954-1972), writes “let my eye speak for me”[iii]. This evokes Pierre Nora’s definition of the Intellectuel, in which revolutionary idealism is outdated; public intellectuals should instead pursue “reflective judgement”[iv]. Michel Foucault calls for the Intellectuel to no longer present themselves as the subject, a saviour of oppressed peoples, and instead utilise their experiences and relationships to relieve oppression[v]. Both insist on the importance of expertise within one’s field: Cartier-Bresson, a founding Magnum photographer and creator of an entire photographic style (Le Bougé Décisif), is undisputed in this capacity[vi]. Furthermore, an affordance of photography during Cartier-Bresson’s time, could be its objectivity of viewpoint. He can capture instantaneous reality in his work, and this objectivity helps add to his expert status, further legitimising his intellectuel status in the eyes of Foucault and Nora.

Cartier-Bresson also aligns with some alternate definitions, such as those of Jean-Paul Sartre, who upheld the militant and radical values of the intellectuel[vii], something which Cartier-Bresson could also claim, serving as an army corporal and spending 35 months in a German POW camp[xiii]. His book Images à la Sauvette is named after this experience[ix]. Furthermore, in a 1969 interview, he stated “la photographie… c’est une arme”; a weapon with which he intended to change the world[x]. Cartier-Bresson’s intellectuel status is solid from multiple perspectives.

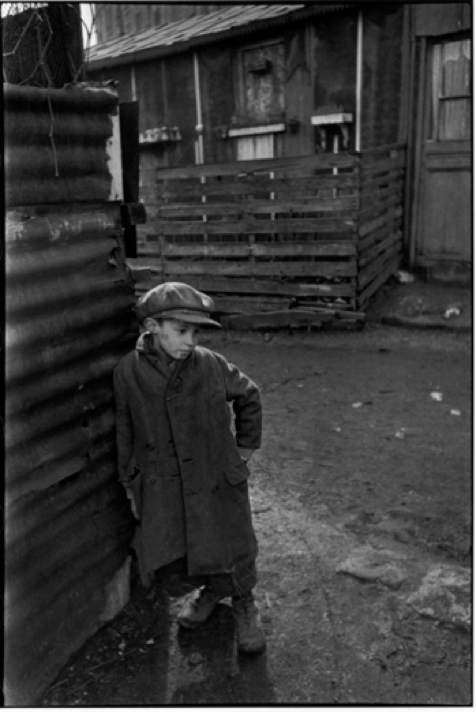

Lastly, idealism and political conscience are core elements of many intellectuel figures, be it existentialism, négritude, Marxism or even Fascism. It is hard to deny the idealism at play within Cartier-Bresson’s work, especially his social realism. The tool we need to lift this political conscience from his work is intermediality, the intersection between mediums as well as each’s natural plurality. For example, Montier describes Cartier-Bresson as an author of images, creating scripts for each of his photographs: much of his work contained meta-narratives, with poetic reflections on reality, branching past the typical genre conventions of photography[xi]. These narratives are overwhelmingly drawn from social realism. Like painter Gustave Courbet, he brought the ‘uglier’ parts of society away from the margins and into the spotlight. Poverty and dereliction were constant features of his work[xii].

This is highly evident in Academician on his way to a ceremony, Notre Dâme, Paris, 1953 (fig. 3).The photograph is indicative of Cartier-Bresson’s signature style, le bougé décisif, capturing in a single moment an image of equally important content and composition[xiii]. Pictured is an academic figure in his ceremonial garb, entering a taxi. Behind him stand three working men, fixated intently on him, three distinct yet subtle judgements on their faces. This interest is singular in direction; the Academic has not noticed his observers, either not knowing or caring about their presence.

To understand Cartier-Bresson’s underlying social commentary, we should situate the work within the narrative of French post-war cultural reconstruction, from 1944 onwards, drawing from writer Michael Kelly’s 2008 article. Kelly describes the ‘rebuilding’ as an imperative; a common task that placed all internal conflicts as secondary[xiv]. He talks of a collective swallowing of pride with “deep-seated reservations” on the part of the working class[xv]. Symbols and myths became the new tools of De Gaulle’s government in their attempt at a ‘DIY’ cultural rebuild, setting the “moral framework” for humanist, Marxist and existentialist arenas of debate[xvi]. Kelley’s description of the period describes a top-down sense of unprecedented unanimity, superseding divisions of class and gender. He writes:

“Now for perhaps the first time in two centuries there was no available cultural identity or political project outside the existing regime”[xvii].

It is this exact sentiment that I believe the photograph problematises.

In thinking that this photograph was captured through instantaneous intuition; no aspect was directed or staged, we can see the intermediality in Cartier-Bresson’s take on the photographic medium. As Marina Grishakova writes, we can see the “aspiration” of the visual affordances of photography to become articulated and distinct[xviii]. The photo’s composition and content contain a rhetoric to be perceived and explained. For example, he plays with one of the key genre conventions of his medium, being a visual subject, through the rhetoric of duality and opposition. The title would lead you to believe our subject is the Academician, his flamboyance and visual distinctness add to this. Yet I find my eyes drawn just as much to the background. It is within our trio of judgemental observers that we find narrative, emotion and intrigue. Why were they excluded from the title? Furthermore, he uses juxtaposition: the image is compositionally split in half, workers on the left, Academician and taxi on the right. Perhaps this mirrors the political alignments of the two parties? The workers are grouped closely in repeating forms, dressed almost identically helping present them as the ‘masses’, whereas the Academician is alone, sharing space with only the mechanical details of a vehicle.

If we view our joint subjects as symbols representing their classes, the working people and elites, we can draw out a political commentary of sorts. The Academician is dressed in black and white, whereas the workers sport a blend of colours, mirroring an elite who might have been treating very nuanced issues of nation-building as just black or white. His apparel is pompous and impractical, whilst the workers are dressed for warmth, perhaps reflecting an overestimation of the necessity for symbolism and myths by De Gaulle’s government. As mentioned, the workers are all fixated on the Academician, yet he takes no notice of their existence; does this represent an elite who stay their course regardless of popular approval, and are building a nation catered to their own tastes? I believe the image aspires past its visual semiotic medium and writes a rhetorical question: Who is my primary subject the workers, the Academician, or both? In our context: Who is this nation being rebuilt for, the masses, the elite, or both?

It is the message at the heart of much of Cartier-Bresson’s photography, which brings us out of the world of myths, debate and symbols and grounds us in characters and humanity. A rhetoric which sparks introspection and reflection by presenting us with a reality devoid of pictorialism. It is the truth presented by Cartier-Bresson. Through capturing the decisive moment, he frames the visual truth in a manner which speaks to us like a text; asking, demanding and asserting. His message is clear, yet, due to its genre, does not over-extend itself, leading us to wonder whether it was intended by the author, or constructed by the viewer. Instead of being morally instructed, we are given a framework in which to draw our own conclusions. I would argue his social realism is more accessible by giving us a certain ownership over its messages, instead of just persuading us into alignment.

This empowering characteristic Cartier-Bresson’s work as an intellectuel was displayed recently with the 2020-21 exhibition Le Grand Jeu, in Venice. The exhibition gathered five co-curators: a collector, writer, director, photographer and curator (Wim Wenders and François Pinault among them) to choose 50 images from Cartier-Bresson’s work, each creating independent exhibitions that stand side by side[xiv]. All at once, this encapsulates the main concepts I have been discussing: foremost, the intermediality of Carter-Bresson’s work. Each co-curator comes from a different cultural medium with different genre conventions; their selections reflect this seeing as the exhibition was intended to tell stories of the curators own work, lives and emotions[xx]. They could dictate the scenography, colour palette and framing of the images, and yet, Cartier-Bresson’s voice, and his social realism, is universal throughout, highlighting his power as an intellectuel[xxi]. By allowing us to tell our own story through his images, his truth always shines through, even today, 20 years after his passing.

Appendix

Fig. 1: Marseille, France, 1932 (Michael, 2006.)

Fig. 2: Aubervilliers, France, 1932 ( Jeffrey, Ian, Kolzoff, 2008)

Fig 3: Academician on his way to a ceremony, Paris, 1953 (ICP, 2018.)

End Notes

- Montier, 2010, p.1.

- ibid. p.6.

- ibid. p.7.

- Kritzman, 2006, p.373.

- ibid, p.370

- Genova, 2019.

- Kritzman, p. 366.

- 2019.

- Jeffrey and Kolzoff, 2008, p.160.

- Feyder, 1969.

- 2010, p.154.

- Cookman, 1998, p.9.

- ibid, p.3

- Kelley, 2008, p.94.

- ibid.

- ibid, p.96.

- ibid, p.98

- Grishakova, 2023, p.15.

- Pinault collection, 2020.

- ibid.

- ibid.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Brenson, Michael, and Thames and Hudson. 2006. Photofile: Henri Cartier-Bresson (London: Thames and Hudson )

Brochure Esecutivo: Henri Cartier-Bresson, Le Grand Jeu. 2020. Pinault Collection (Venice: Marsilio Editori), pp. 1–36 <https://www.pinaultcollection.com/palazzograssi/media/dl/hcb_brochure_esecutivo.pdf> [accessed 28 October 2024]

Cookman, Claude. 1998. ‘Compelled to Witness: The Social Realism of Henri Cartier-Bresson’, Journalism History; Las Vegas, 24.1: 2–15 <https://www.proquest.com/docview/205356779?sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals> [accessed 14 October 2024]

Feyder, Véra . 1969. ‘Henri Cartier-Bresson’ (Office national de radiodiffusion télévision française) <https://www.ina.fr/ina-eclaire-actu/audio/phd99208715/henri-cartier-bresson> [accessed 15 October 2024]

Feyder, Vera , and André Pieyre de Mandiargues. 1998. Henri Cartier-Bresson: à Propos de Paris, 1st edn (237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017: Bulfinch Press)

Genova, Alexandra. 2019. ‘The Liberation of Paris from Nazi Rule • Magnum Photos Magnum Photos’, Magnum Photos <https://www.magnumphotos.com/newsroom/conflict/the-liberation-of-paris-from-nazi-rule/>

Grishakova, Marina. 2023. ‘Intermediality: Introducing Terminology and Approaches in the Field’, ed. by Jørgen Bruhn, Asunción López-Varela, and Miriam (Springer International Publishing), pp. 1–17 <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91263-5%E2%82%812-1>

Jeffrey, Ian, and Max Kozloff. 2008. How to Read a Photograph : Understanding, Interpreting and Enjoying the Great Photographer, 1st edn (London: Thames & Hudson), pp. 152–62

Kelly, Michael. 2008. ‘War and Culture: The Lessons of Post-War France – EPrints Soton’, Synergies Royaume-Uni et Irland: 91–100 <https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/80106/1/kelly_synergies.pdf>

Kritzman, Laurence D. 2006. ‘The Intellectual’, The Columbia History of Twentieth Century French Thought, ed. by Laurence D. Kritzman, Brian J. Reilly, and M. B. DeBevoise: 363–74

‘Libération de Paris, Rue Saint Honoré, France, 22-25 Août 1944 | Pinault Collection’. 2020. Pinaultcollection.com <https://lesoeuvres.pinaultcollection.com/en/artwork/liberation-de-paris-rue-saint-honore-france-22-25-aout-1944> [accessed 28 October 2024]

Montier, Jean-Pierre , and Franck Le Gac (Translator). 2010. ‘Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Public Intellectual”?’, Études Photographiques [Online], 25: 1–14 <http:// journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/3449 > [accessed 10 October 2024]

Office national de radiodiffusion télévision française, and Jean Marquet. 1974. ‘Henri Cartier Bresson à Propos de Son Livre Sur l’URSS | INA’, Ina.fr <https://www.ina.fr/ina-eclaire-actu/video/i14010630/henri-cartier-bresson-a-propos-de-son-livre-sur-l-urss> [accessed 15 October 2024]

Paris. 2018. ‘Academician on His Way to a Ceremony, Paris’, International Center of Photography <https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/objects/academician-on-his-way-to-a-ceremony-paris> [accessed 13 October 202