Les Insoumuses ‘Maso et Miso vont en bateau’ (1976) and the use of video as a second- wave feminist tool

‘No image on television wants to or can reflect us. It is through video that we will recount our lives,’ declare 1970s French Feminist Video Collective, Les Insoumuses, in one of the final frames of their 1976 ‘Maso et Miso vont en bateau’.[i]

This final message highlights the central purpose behind the work of Les Insoumuses: to use video as a vehicle for political activism, to tell the real stories and struggles faced by women, a representation not afforded to them through institutionalised mediums such as film and television.

This post will highlight the work of Les Insoumuses with a particular analysis of their 1976 work ‘Maso et Miso vont en bateau’ a hijacked and edited version of a popular French talk show used to draw attention to, and mock the pervasive misogyny in French mainstream media.

The video collective: ‘By women, for women’

The opening credits shown in ‘Maso et Miso’ cite only ‘Les Insoumuses,’ moving away from the traditional format in film and television of longer opening credits. In a 1973 interview, Carole Roussopoulos, of Les Insoumuses declared that this choice was intentional.[ii] Indeed, the use of long opening credits ‘was associated with apolitical use of video.’[iii] Therefore, the collective accreditation, immediately categorises Les Insoumuses’ videos as political work. Rather than conveying a singular viewpoint and personal narrative, collective authorship denotes the idea of ‘we’ suggesting a group cause and representative voice.[iv]

Indeed, from the release of the Sony Portapak (handheld) camera in 1969 for public purchase, video was almost ‘immediately conceived as an instrument for militant action.’[v] It was also a distinctly female medium with the collective VIDEA declaring: ‘we claim video as a feminist intervention. By women for women.’[vi]

The characteristics of video provided an accessible medium for activists to work. Transportable, easy to use and relatively affordable compared with film, especially when funded by a collective, it ‘liberated women from financial [and technological] dependency’ on more formal modes of production, which were dominated by men. Furthermore, the ease with which one could edit and reshoot video allowed women to control their image, which was usually constructed in the media by the male gaze.

Most importantly, as an emerging form of media, video was, according to Roussopoulos, ‘a new medium which hadn’t been colonised by men and their power.’[vii] This allowed women creative freedom and a way to provide an alternative feminine narrative to the male- centric discourses dominant in film and television. Perhaps, this can be considered an intermedial implementation of feminist Helene Cixous’ theory of ‘l’écriture féminine’ in which she emphasised the importance of women finding their own modes of expression away from patriarchal norms.[viii]

Given the wider context, with the foundation of the Mouvement de libération des femmes in 1970, and ideas brought by second wave feminism of ‘porter la parole’ (speaking up) popularised by Simone de Beauvoir and Le Torchon Brule magazine, the 70s provided an unprecedented platform for the diffusion of Les Insoumuses work in a world that was beginning to open up for them.[ix]

‘From muse to insoumuse’[x]

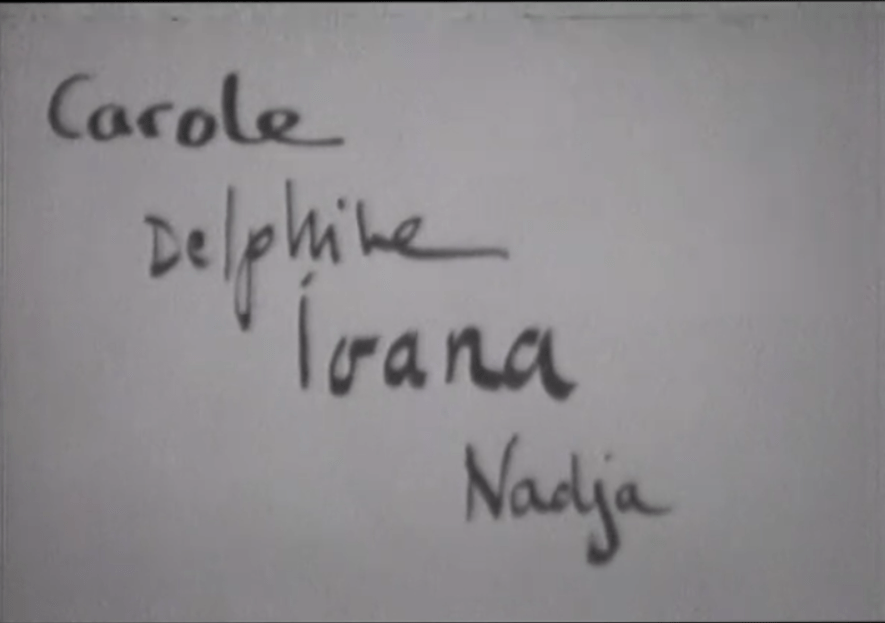

Les Insoumuses were founded in 1974 by Carole Roussopoulos, Delphine Seyrig, Ioana Wieder and Nadja Ringart. Their name is a fusion of ‘insoumise,’ which translates as disobedient or defiant and, muse. Therefore, meaning ‘Defiant Muses.’[xi]

This self-proclamation of ‘Defiant muse’ is significant. Arguably the most prominent member of Les Insoumuses was Seyrig, whose fame drew attention to the collective. She was best known as an actress, notably from Resnais’: ‘Last Year at Marienbad,’ (1961) where she would appear as a muse curated by the male gaze, as was the default for women in film at the time.[xii] In an age where out of ‘nearly 150 filmmaker’s’ in the Nouvelle Vague none of them were women, the act of a woman going behind the camera to produce video was, indeed, defiant.[xiii]

The videos produced by Les Insoumuses also defied norms. These include a re- interpretation of the radical feminist, famous for her attempted assassination of Andy Warhol, Valerie Solamas’, SCUM Manifesto, as well as interviews with a series of women in the film industry in Sois belle et tais-toi who all highlighted similar frustrations about their objectification and lack of control in their media portrayal. Video was therefore a vehicle through which unheard voices, perspectives and demands could gain a platform.

Maso et Miso vont en bateau

In 1976, Les Insoumuses produced their most famous work: Maso et Miso vont en bateau. The video is an edited version of a 1975 talk show episodeentitled ‘Encore un jour de l’Année de la femme. Ouf! C’est fini!’ In this episode, Bernard Pivot, who had been presenting Apostrophes, invited Francoise Giraud, the French Secretary of State for the condition of Women, to react to a series of misogynistic video clips and statements made by prominent figures in popular culture at the time in order to joke about the end of the 1975 UN Year of Women.[xiv]

Instead of rebutting the statements, Giraud laughs along and sometimes even defends them. Highlighting how women must often accept masochist (maso) or misogynistic (miso) norms in order to gain positions of power.[xv] To take one example, in one clip shown on the original show, the idea of women working as professional chefs is mocked. Giraud defends the sentiment, declaring that she did not believe women could manage the demands of the job.

Using the new editing techniques made available through video, each time a misogynistic statement is made, Les Insoumuses issue an interjection.[xvi] These interruptions are often in the form of placards (see Fig 3) to correct and refute statements made during the programme, as well as pauses or repetitions of absurd statements for dramatic effect, voice overs and sound effects. In one part, where Giraud is defending the responsibility of women being to raise children, Les Insoumuses add the increasingly desperate voice of a child repeatedly nagging ‘Maman!’ giving the effect of a child begging their mother to stop saying something embarrassing.

The interjections have humorous and hyperbolic effect, drawing to attention the ‘idiocy’[xvii] of what is being said as well as giving ‘the women the last laugh.’[xviii] They are also symbolic, with the physical interruptions also reflecting Les Insoumuses wider intentions to disrupt (physically and symbolically) the dominant misogyny presented on television with video.

New forms of rhetoric: Maso, Miso ou les deux?

The rhetorical elements of Maso et Miso are highly effective and innovative.

The placards shown often appeal to the viewer directly, asking rhetorical questions or asking the viewer to choose from multiple options.

This technique confronts the viewer directly, forcing them to ask and consider the validity of the narratives they are being given by television and dominant forms of mainstream media.

Maso and Miso’s most powerful tool is its humour. It is through poking fun and comedic effects, that Les Insoumuses dismantle and expose the misogyny shown on television in a way which is both hilarious and engaging, in a sense, they are ‘cackling in the face of the patriarchy.’[xix] The impact of this technique should not be minimised. Upon release, Maso et Miso gained such wide popularity that Giroud attempted to stop distribution.[xx] Today these techniques, with social media and, editing tools easily accessible, creating memes, parody videos and voice overs are a prominent political tool used for engagement.[xxi] Whilst common today, in 1976, Les Insoumuses methods were highly radical, and clearly stuck.[xxii]

Conclusion

The work of Les Insoumuses demonstrate how video became the medium through which women could represent themselves. Whilst television and film were already dominated by the male gaze and misogynistic norms, video allowed creative and ideological freedom.

Maso et Miso carries this idea to its very end. The final credits use just the first names of Les Insoumuses. By rejecting norms seen in male dominated mass media, video gave them their own ways of expression and forming their own narrative- the ‘Ecriture feminine’ of visual media.[xxiii]

Bibliography

Centre Audio- visual Simone de Beauvoir, (1976) Maso et Miso vont en bateau, https://www.centre-simone-de-beauvoir.com/produit/maso-et-miso-vont-en-bateau/

[Fig 1] Delphine Seyrig et Carole Roussopoulos (1975), Troiscouleurs, https://www.troiscouleurs.fr/article/portfolio-delphine-seyrig-et-carole-roussopoulos-camera-au-poing (03/11/2024)

[Fig 2] Resnais, A. (1961)Delphine Seyrig: Last Year at Marienbad, https://classiq.me/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/delphine-seyrigs-style-last-year-at-marienbad-8-e1349333627622.png (05/11/2024)

[Fig 3] Maso et Miso vont en bateau, (1976), http://femlumagazine.ca/maso-et-miso-vont-en-bateau-les-insoumuses/ https://www.centre-simone-de-beauvoir.com/produit/maso-et-miso-vont-en-bateau/ (05/11/2024)

[Fig 4] Centre Audio- visual Simone de Beauvoir, (1976) Maso et Miso vont en bateau, (27 :21) https://www.centre-simone-de-beauvoir.com/produit/maso-et-miso-vont-en-bateau/

[Fig 5] Ibid, (54 :41)

Further Reading

An, G. (2019) From Muse to Insoumuse: Delphine Seyrig, Vidéaste, in Margaret Atack, and others (eds), Making Waves: French Feminisms and their Legacies 1975-2015, Contemporary French and Francophone Cultures LUP (Liverpool, 2019; online edn, Liverpool Scholarship Online, 21 May 2020), https://doi.org/10.3828/liverpool/9781789620429.003.0004.

Hogeveen, E. (2019) Speaking and Recording and Broadcasting their truths, https://brooklynrail.org/2019/04/film/Speakingand-Recording-and-BroadcastingTheir-Truths-A-timely-exploration-of-second-wave-French-feminist-video-in-Callisto-McNultys-Delphine-and-Carole/(21/10/2024)

Holmes, D. Long, I. (2019) 1975 The Year of Women, in Margaret Atack, and others (eds), Making Waves: French Feminisms and their Legacies 1975-2015, Contemporary French and Francophone Cultures LUP (Liverpool, 2019; online edn, Liverpool Scholarship Online, 21 May 2020), https://doi.org/10.3828/liverpool/9781789620429.003.0003

Hudson, D. (2022) Delphine Seyrig and the Defiant Muses, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7750-delphine-seyrig-and-the-defiant-muses (05/11/2024)

Hyams, R. (2019) Exhibition: How 1970s French feminists harnessed innovative media tech https://www.rfi.fr/en/culture/20190805-france-culture-1970s-feminist-revolution-technology-media-paris-film-culture (24/10/2024)

Jeanjean, S. (2011) Disobedient Video in France in the 1970s: Video Production by Women’s Collectives, https://www.afterall.org/articles/disobedient-video-in-france-in-the-1970s-video-production-by-womens-collectives/(30/11/2024)

Lebovici, E. Zapperi, G. (2018) Maso and Miso in the Land of Men’s Rights, E-flux journals, Issue 218, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/92/205771/maso-and-miso-in-the-land-of-men-s-rights/

Leprince, C. (2023) Comment Delphine Seyrig et Carole Roussopoulos ont fait la révolution armées d’une camera, Culture France, https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/comment-delphine-seyrig-et-carole-roussopoulos-ont-fait-la-revolution-armees-d-une-camera-4911706 (05/11/2024)

Murray, R. (2016) Raised Fists: Politics, Technology, and Embodiment in 1970s French Feminist Video Collective, Duke University Press, Camera Obscura (2016) 31 (1 (91)): 93–121. https://doi.org/10.1215/02705346-3454441 .

Museo Reina Sofia, (2019) Delphine Seyrig and the Feminist Video Collectives in France in the 1970s and 1980s https://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/exhibitions/defiant-muses (01/11/2024)

Pecourt, J. (2023). Feminist counterpublics and media activism in contemporary France. Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2023.2220081

Sørensen, Majken (2017) Laughing on the Way to Social Change: Humor and Nonviolent Action Theory. Peace & Change 42(1):128-156

Wald, J. (2024) There’s research on that: Humour and Memes in Politics, The Society Pages, https://thesocietypages.org/trot/2024/11/05/humor-and-memes-in-politics/ (05/11/2024)

Winter, R. (2024). Becoming a Vidéaste: Media Practices Between Collectivity and Strategic Claims of Directorship in French Feminist Video Activism. Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509208.2024.2398946

[i] (An, 2019)

[ii] (Internationales Forum des Jungen Films, 1973)

[iii] (Winter, 2024)

[iv] (Ibid)

[v] (An, 2019)

[vi] (Ibid)

[vii] (Winter, 2024)

[viii] (Cixous, 1975)

[ix] (Winter, 2024)

[x] (An, 2019)

[xi] (Hudson, 2022)

[xii] (Museo Reina Sofia, 2019)

[xiii] (Winter, 2024)

[xiv] (Leprince, 2023)

[xv] (An, 2019)

[xvi] (Murray, 2016)

[xvii] (Murray, 2016)

[xviii] (Hogeveen, 2019)

[xix] (Ibid)

[xx] (Murray, 2016)

[xxi] (Wald, 2024)

[xxii] (Murray, 2016)